The scientist paving the way for girls in STEM in Canada, Larissa Vingilis-Jaremko

Larissa Vingilis-Jaremko is the Founder & President of the Canadian Association for Girls in Science (CAGIS), Canada’s largest and longest-running STEM club for girls, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming youth aged 7-16. With virtual programming and local clubs that visit labs, workshops, and field sites to meet mentors and do fun, hands-on activities, their aim is to inspire the next generation of girls in STEM in Canada.

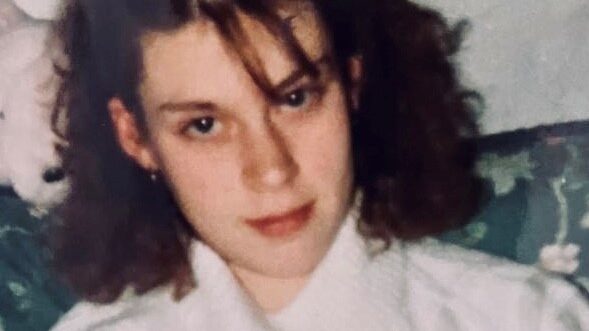

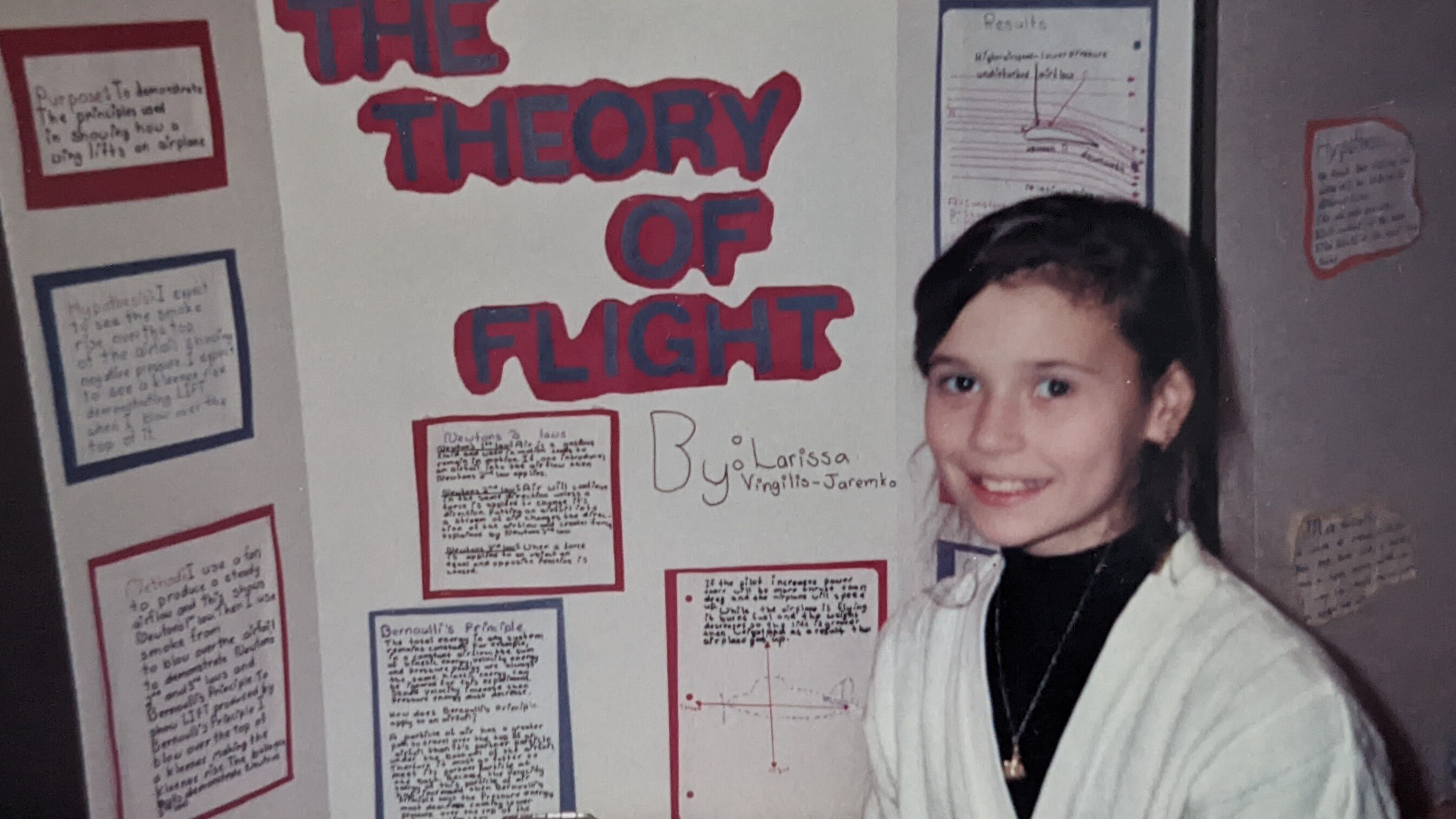

With a natural curiosity from a young age and an interest in science and engineering that had been carefully nurtured and encouraged by her parents, Larissa initially had the idea for CAGIS at just nine years old and knew that she wanted to pursue a career in STEM.

For PathFinders, we spoke to her about her career journey, her goals with CAGIS and much more.

Tell us about your early years, when did your interest in STEM first appear?

When I was younger, I was kind of interested in everything. I was a very curious kid. I just wanted to discover and explore and learn. I always had a lot of questions and I discovered, thanks to my parents, that science was a great way to answer questions. When I had these millions of questions, as most kids do, my parents would help me through the scientific method.

My mom is a scientist, she currently works as a professor at Western University and her area of expertise is adolescent at-risk behaviour. My dad was a mechanical engineer and a pilot. So, I got very different types of STEM training from both. On my dad’s side, it was a lot of aviation and building and mechanical stuff. And on my mom’s side very much the research methods, the scientific method. It was a nice balance from them.

We would build things, we would do research. You know, the normally the step one is to start off by reading books and seeing ‘what do we know about this topic?’ But then we would also do experiments where we bring leaves and dirt home. I would prick my finger and look at blood under my microscope. I would explore a lot and science and engineering and tech were just great ways of fulfilling that curiosity I had.

How was school for you? Did you know what you wanted to be from a young age?

I wouldn’t say that I knew exactly what I wanted to be. I was interested in so many different things. I liked science and engineering, but I also love to dance. I wanted to be an astronaut and a lawyer and a professional dancer. I wanted to be all of the things! But STEM was part of that.

In high school I knew I needed to take the science courses, especially with parents who were in STEM. I did just kind of a general science and I ended up focusing on psychology, biology and French as a minor.

Through that, I was debating what path I wanted to take. I ended up in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience and Behaviour. I was really interested in vision science from a cognitive perspective, how the brain processes visual information and how that is affected by visual experience and different typical versus atypical visual experience in development.

I ended up doing my PhD in that. I did some post-doc work and after a few years of post, I was running my organisation, the Canadian Association for Girls in Science, on the side until I saw a grant that was a really good fit, so I applied for it. We were successful and then that actually allowed me to leave academia, which was a hard decision because I love academia. But we have been successful with continuing to get funding so far and we now have a small team of staff in addition to hundreds of volunteers across the country.

What negative stereotypes did you see in school that inspired you to help girls in STEM in Canada?

As I mentioned, I loved science and engineering as a kid because I got to do it in a very hands-on way at home. When I was in school, I saw that a lot of the kids, particularly the girls in my classes, had very different perceptions. They had stereotypes. The typical scientist stereotype, an old white man with wild hair glasses, a lab coat. The perceptions were also that people in STEM were kind of nerdy. They like to stay in their lab. They didn’t socialise, they didn’t have any other interests. These were negative perceptions that were turning a lot of the girls off the subject entirely. For many of them, it was their least favourite subject.

At school, it was very book-learning-related environment. It was a way of exploring it that was different from what I found fun at home, it was different to the way my parents were facilitating that interest in me, so I knew that there was a stereotype that I wanted to break. For example, one day when I was in Grade 4, my teacher had said to our class, “I need a volunteer to set up this experiment really quickly from this science kit. Can I have a volunteer?” Now I have the science kit at home. I knew I could do it really quickly, so I raised my hand and she said “No, Larissa. I need a boy to do this.”

So I started to invite the colleagues of my parents into my classroom, women in science and engineering to be role models and to do some fun, hands-on activities with us so that the other girls in my class could see that the stereotypes aren’t true and STEM can be really fun.

When did you first get the idea to form CAGIS, and why?

My mum was actually involved in the Canadian Coalition of Women in Engineering, Science, Trades and Technology (CCWEST) when I was young, back in 1992. Sometimes I was bought along to it when it was a conference. Instead of pushing me as a kid into the corner, they brought me up to the board table and asked me questions like, ‘what are things like for you as a girl in STEM in Canada?’ and ‘What do you think needs to change. what are things like in your classroom?’.

And so one day I stood up at one of these meetings when I was nine and said I’m going to start an organisation for girls. This is what I plan to do, and they were all really supportive. That gave me the part of the inspiration and the confidence to start. I think because I saw all of these other women who were doing these great things and who were trying to fix the problem.

What is CAGIS and what does it do?

CAGIS is a STEM club for girls and gender diverse youth. It has two main programmes. One of the programmes is our local clubs, or chapters, which we have all across the country. Every month we go on a mini adventure to a different STEM location. These adventures are around 2 hours in length and we get to do fun things like sample fish in a pond. We catching the fish and colleting data with the scientist or we might go to a garage and work with the mechanic and learn how to tune up cars. We’re always going to these really cool locations to do exciting STEM activities to really encourage girls in STEM in Canada.

Then there are our virtual programmes. These happen every week during the school year. There are two one-hour sessions, one for kids, one for teens. Again, we make sure that there are role models present who are STEM experts learning the activities. They’re very hands on, so we might be making ice cream with a food engineer or growing crystals with a chemist. Again, most of the sessions are hands on because that’s the main component that we want to make sure we’re incorporating.

Organisations like CAGIS are doing a lot to balance out the gender divide and encourage girls in STEM in Canada. How do you think the perception of STEM subjects has changed since you were young?

I wish it had changed more. Unfortunately, we’re still seeing the same stereotypes in full force. I think there have been some shifts because one of the main places we get these stereotypes is from the media and from society at large. In the media, we are seeing more women and gender diverse people represented in STEM. So that’s a great step.

There is a task where scientists ask kids to ‘draw a scientist’. And then they rate the drawings based on the stereotypes that are present. We’ve have found that the stereotypes present have reduced over time and the percentage of women scientists that are being drawn by kids has increased. In fact, among 5 to 6-year-olds, they’re drawing equal numbers of male and female scientists, so that’s a great step. But we’re also seeing that as kids get older, by the time they’re 13 or 14, the number of male scientists being drawn are outnumbered 4 to 1. And so that’s kind of an important thing for us to know and that’s why developmental research is so important to make sure that we’re looking across ages.

What would you say the biggest challenges specifically in Canada at the moment with regards to attracting girls into STEM?

If we think of gender equity in STEM as a pipeline, it starts with youth. Making sure that those educational barriers are not present and that we are able to support youth in their education up to post-secondary and beyond. But it continues once we’re looking at the STEM workforce. Making sure that the workforce and the companies and employers are creating equitable spaces for their employees. And then the third component is advancement. We know that women and gender diverse people hit what we sometimes refer to as a glass ceiling. They’re not advancing in their careers at the same rate as men are. And we know that that this is impacted by bias.

There was a study that was done where University professors were given a job application for a lab manager, and they changed the name on the job application from Jane to John and had the university professors rate the job applications with the two names based on which one was more qualified, who was more hireable, etcetera. They found that when the name was a male name that those applications were rated as more qualified, assigned to higher starting salary, assigned more mentorship. They were the same application. And so that’s an example of how this bias this would be an example of implicit bias, how it affects trajectory of youth and adults within STEM.

What are the future plans for CAGIS?

With our local clubs, there continues to be a lot of interest across the country, both from places where we currently have local clubs or chapters and places where we don’t. Our plans are to be able to expand to make sure that we’re meeting that demand and that need and to start local clubs in regions where there’s interest where we don’t currently have them. As far as our virtual programming goes, we want to make sure as many people know about it as possible so that they can join in. We have also a fun new portion of our website that will be launched soon which will involve fun hands-on activities, blog posts written by youth, videos, a more interactive, ongoing way that you can participate in STEM.

If they don’t, if they aren’t able to log on at the right time of our virtual sessions or in person, so it’s just kind of an additional enrichment of our programming.